Short and Punchy

Some people probably think you go to school, or take courses, to learn how to write.

While those are viable (developmental) options, I think you’re learning all the time.

While those are viable (developmental) options, I think you’re learning all the time.

You learn through reading, and I used to read lots. I’d study the way the story was structured; how the punctuation functioned; the way the sentences told the story; the voice behind the story; how many characters there were, what each did, etc.

TV and movies are also good educators, particularly in how structure works.

And you pick up things from all sort of sources, or they influence the way you do things.

When I was a kid, my writing suffered from overlong sentences trying to do too much. I see this a bit with inexperienced writers, sentences like:

I went to the shop and bought a milkshake that was chocolate and on the way home I saw my friend Jim and he wanted to go to the park so we had a kick of the football until it was time to go home and have dinner until I realised I’d forgotten my milkshake at the park.

This isn’t even that horrific. You understand what’s being said. Sometimes, that’s not so clear. You’re wondering how the action has gone from one part of the sentence to the next. But for the purposes of an example, the above is fine.

My Year 7 English teacher, Bryan (we addressed teachers by their first name), identified my robust clunkiness, and taught me to identify each thing I was saying by breaking sentences down into each component.

So, in this example:

-

-

- I went to the shop

- bought a chocolate milkshake

- saw my friend Jim (on the way home)

- he wants to go to the park to play football

- we go to the park and kick the ball around

- I go home

- I have dinner

- I’ve forgotten my milkshake at the park.

- I went to the shop

-

I’ve taken the breakdown further here by ordering a hierarchy.

We now understand every single thing that’s happening in this sentence, what’s the primary action and what’s subordinate to it, and how structurally the narrative should unfold.

I’ve seen some editors just leave an overlong sentence, or start connecting shorter sentences with the use of “and”, although there’s no causal linkage (or evolution) between the separate parts. It’s really shitty editing, clunky as fuck, and lacks an understanding of how the narrative is working. (This is me getting old-man ranty. Or rantier.)

The above example could read:

I went to the shop and bought a chocolate milkshake. On my way home I saw my friend Jim; he wanted to go to the park so we could kick the football around. We did that until it was time for me to go home for dinner. It wasn’t until I started eating that I realised I’d left my milkshake at the park.

The primary beauty of writing (in my opinion) is that we’re all unique, so we could all phrase this passage uniquely, and each version should be equally valid. But validity is a sphere that accommodates a lot of options – a lot, but not every option. Outside the sphere, things can be shit.

Bryan teaching me what he did has always stayed with me, and is a driver behind my writing and editing.

It doesn’t mean all my sentences are “short” and “punchy” (as they’re sometimes described), but they’ll at least be airtight in what each is trying to say.

This is also an example of how we have lots of different teachers as a writer. We cannibalize what we need, amalgamate it, and filter it through our own voice.

The methodology behind learning how to apply all this is simply to write – that is, we just have to sit down and do it. All the theory means nothing until it’s put in practice.

I was (and still am) always practicing.

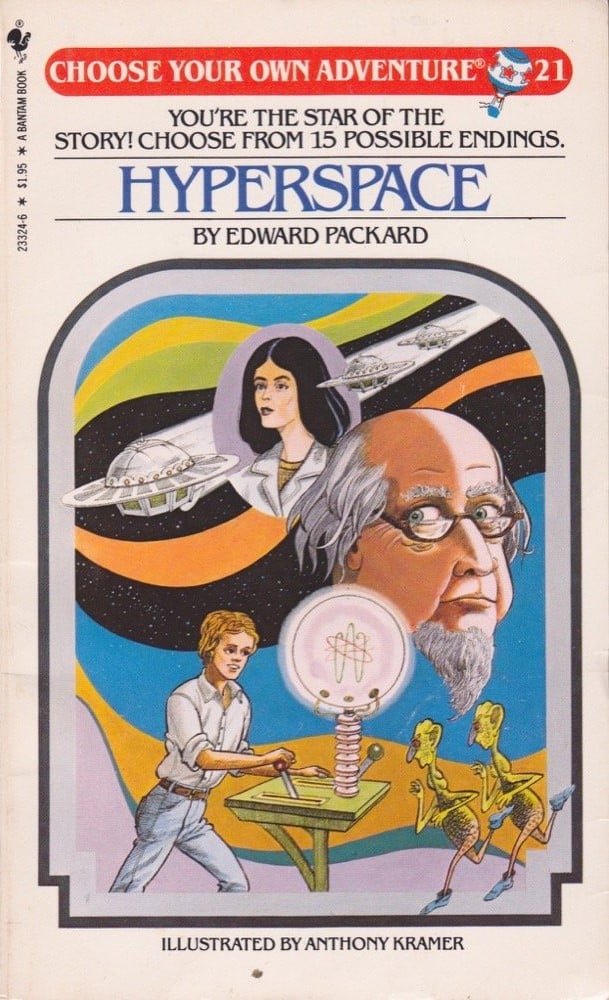

In high school English, I churned out epic stories – one of our assignments in Year 8 English was writing a Choose Your Own Adventure story. Mine was like a cross between James Bond and Rambo, and had about 120 entries. I used to lay them down on the floor of my bedroom to diagram the story.

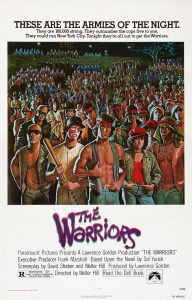

We had to write a play at one stage, and I ripped off The Warriors movie (like most kids, I was easily influenced), but wrote all these additional scenes.

We had to write a play at one stage, and I ripped off The Warriors movie (like most kids, I was easily influenced), but wrote all these additional scenes.

Throughout high school, whenever we were given creative license, I’d write these big, big stories. In Year 9 English, I wrote the backstory for a Commodore 64 game I was playing at the time. The teacher recoiled when she saw it was sixty pages. Then I’d write second drafts nobody asked for, expanding on the story.

Even with all this happening, I didn’t immediately realise what I wanted to do once I finished school. Most teens are clueless; I was dealing with the onset of mental health issues, too, so that clouded things. Nobody in school identified I should pursue creative writing. In the 1980s, I don’t even know what pathways existed. So I was left to my own devices.

As I got older (like sixteen), I wanted to play in a band and learned lots of chords on a lead guitar. I wrote lots and lots of shitty lyrics, and envisioned how the music videos would play out.

I also wanted to write computer games – the gaming market was still frontier territory in the 1980s. And games were usually the produce of one programmer, rather than the mega collaboration they are now. I could see how the games would play out, and the story that offered them context.

Both pursuits shared a common denominator: the story behind what was happening. That’s what really drew me – the storytelling component.

Eventually, that became my thing: I wanted to be a storyteller.