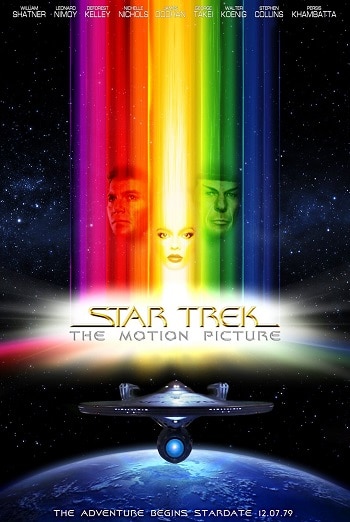

A Look Back: Star Trek – The Motion Picture

Before looking back at Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), I have to go back even further for context.

The original pilot for Star Trek: The Original Series (1966 – 69), “The Cage” didn’t sell because it was considered too cerebral.

Out went Captain Christopher Pike (Jeffrey Hunter) as the commanding officer of the USS Enterprise 1701, and in came Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner) for the new pilot as the series became a little more action-oriented.

The struggles of The Original Series – including the letter-writing campaign that resurrected it after it had been axed following season two – have been well documented. But it lasted only one more season.

Come the mid 1970s, the concept was going to be resurrected with Star Trek Phase II, a series that brought all (the cast) but Leonard Nimoy (who was in dispute with creator Gene Roddenberry and Paramount) back, as well as introducing three new characters in Executive Officer Willard Decker, Science Officer Lt. Xon, and navigator Lt. Ilia.

But then Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) came out and was an enormous hit, popularising science-fiction in the cinematic landscape.

Everybody who could tried to cash in with their own fare, including Paramount, who ditched Star Trek Phase II and decided to resurrect The Original Series through a movie.

That movie was Star Trek: The Motion Picture.

The Plot

A tremendous energy cloud containing the entity V’Ger is heading towards Earth, destroying everything in its way.

The Enterprise has just undergone a refit, and will be launched under its new commanding officer, Captain Willard Decker (Stephen Collins), to intercept. James Kirk, now an admiral, finagles command and temporarily demotes Decker to Executive Officer for the mission.

Spock (Nimoy) is on Vulcan undergoing a ceremony that’ll rid him of the last vestiges of emotion. Across the light years, the entity appeals to his human side on a psychic level. Spock stops the ceremony and eventually re-joins the Enterprise.

Decker’s former lover, a Deltan named Ilia (Persis Khambatta), is also onboard. When V’Ger scans the Enterprise, it seems to disintegrate Ilia. She’s then returned as an emotionless mechanical replication to be V’ger’s mouthpiece, but she also expresses a softer side towards Decker.

The crew eventually discover that the entity is Earth’s Voyager 6 probe, which was damaged and landed on an alien planet. The aliens repaired it so it could complete its mission. On its return to Earth, it accumulated so much information that it amassed consciousness. But for all its intelligence, it lacks the human element to explore concepts beyond scientific proof, and thus wants to merge with its Creator.

Due to his love for Ilia, Decker merges with the entity, it evolves, and Kirk takes the Enterprise out for a spin.

The Update

Robert Wise – who’d directed West Side Story (1961) – was appointed director of The Motion Picture, and treats the subject material with reverence.

The concern is too much reverence.

Star Trek: The Original Series is a product of the 1960s. By 1977, Star Wars had pioneered ground-breaking special effects that were wowing everybody. Now Star Trek wanted a taste, but often there are slow, long shots of the Enterprise, ship operations – such as docking shuttlecraft – and V’ger’s energy cloud.

It’s hero worship for audiences who want to enjoy their Star Trek universe as painstakingly and lovingly as possible, but could’ve benefited from some moderation in some cases, and clarity in others.

The Look

In jumping from the small screen to the big screen, Star Trek got some upgrades.

The ship and the bridge look great.

The Klingons went from dark, bearded men to having ridged foreheads – they now look like the brutal warrior culture they’re meant to be.

Other things didn’t enjoy the transition.

The uniforms in The Original Series were colour-coded. Perhaps it was considered too colourful. In The Motion Picture, everybody is now wearing bland grey uniforms.

In The Original Series, the communicator was this little flip-top thing – like a flip phone. Now the crew wear Dick Tracy-like communication watches.

The filmmakers succeeded when they evolved source material, but didn’t fare as well where they changed it outright.

Kirk

Credit to Roddenberry for building on The Original Series, rather than just rehashing it by sending the crew out on another random mission. Bones (DeForest Kelley) has left Starfleet, Spock has returned to Vulcan, and Kirk has taken a promotion to admiral.

Given Kirk’s string of exploratory and combat successes, you’d expect that he would be promoted. But he’s uneasy in himself, having given up his passion: command. It’s what motivates him to regain command of the Enterprise. And, ultimately, it adds a nice counterpoint when Decker decides he’ll merge with V’Ger.

The Tone

Roddenberry was able to be truer to his original vision of Star Trek – as he was with Star Trek: The Next Generation (1987 – 1994) – with The Motion Picture, which is why it doesn’t entirely feel like a TOS movie.

It feels like the unused pilot, “The Cage”, or the sort of movie TNG should’ve made.

Actually, when you compare TMP to TNG, you see a lot of similarities:

- TMP: Decker is the capable, proactive Executive Officer.

- TNG: William Riker (Jonathan Frakes) is the capable, proactive First Officer.

- Both shield and challenge their respective captains as required.

- TMP: Decker had a relationship with an alien woman, a Deltan by the name of Ilia, before coming aboard the Enterprise, only to find her stationed aboard the same ship.

- TNG: Riker had a relationship with an alien woman, a Betazoid by the name of Deanna Troi (Marina Sirtis), before coming aboard the Enterprise, only to find her stationed aboard the same ship.

The tonal incongruity isn’t wholly inconsistent with The Original Series (or the other movies), but it does feel like a much more cerebral adventure than they would usually enjoy.

Kirk is a swashbuckling hero, but he’s sedate here. He still showcases his typical bluster, but at times seems more commensurate with TNG‘s Captain Jean-Luc Picard (Patrick Stewart).

Where are you, V’Ger?

Various incarnations of Star Trek have introduced cool concepts: the conclusion of TMP has Decker and V’Ger merge and evolve into a new life form that disappears.

What happens to it?

I’ve always thought any Star Trek that follows TOS’s timeline (excluding the new shit) could call back to TMP and explore what became of that lifeform.

Conclusion

Star Trek should be epic in scope because it deals with epic themes. Most of those themes explore the human condition, and how humans respond under pressure and to challenges. They are meant to be a template for us. Idealistic? Probably. But it’s one of the few science-fiction portrayals of our future which isn’t dystopian. Humanity grows up instead of blows itself up. Yeah, I know – hard to believe. (In fairness, Star Trek‘s humanity does both.)

An entity that could destroy Earth is epic in its scale, but the adventure – at times – is too slow. It’s trying to give fans the opportunity to revel in this cinematic universe, but sometimes it does so at the sacrifice of pacing. I’m happy with stories to take their time to unfold and to build the plot, but at times TMP is indulgent.

It also begs other questions. At the beginning, we see Klingons attempt to destroy V’Ger. Given V’Ger is on a course for Earth, why are the Klingons interfering? Did it go through Klingon space? How does the Klingon Empire respond to the destruction of their ships? What else was destroyed on V’Ger’s journey? Why does it again come down to the Enterprise, an older ship that’s just been refitted and is still in dock? Where are the other Starfleet ships? When the Enterprise is inside the V’Ger energy cloud, is V’Ger still consuming everything it encounters?

Fans speculate that V’Ger was repaired by the Borg – the primary antagonists from TNG, a cyborg-culture who assimilate other civilisations and integrate their biological and technological distinctiveness.

Does TMP need a greater exploration of where V’Ger has come from? It tries to generate the same mystique as 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), but the abstract works with 2001, whereas Star Trek has always been about finding answers.

This is not to say that Kirk and company should’ve learned everything about V’Ger’s saviours, but the story at times feels myopic. 2001 poses questions. We interpret what we’ve seen and draw conclusions filtered through our own experiences and understanding of humanity, and where humanity might go. TMP forces us to speculate based on its mystery. We know only what we see. Everything else is guesswork. That answers are extrapolated to link to an antagonist who wouldn’t be created and seen for another ten years – evidence of a lack of any genuine foundation.

In the end, the whole story comes down to a smudge on Voyager’s nameplate. Is that how simply V’Ger defines itself? Or did its rescuers define it that way? These are other questions they could’ve explored further.

You have to give TMP leeway as it tentatively feels its way in adapting its small screen material for the big screen but, ironically, it was an outsider who’d never seen The Original Series, in Nicholas Meyer, who would watch every episode, and arguably be more faithful to its cinematic reinterpretation with Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982).