15

I lay in bed, growing so stifled a fine sweat forms across my brow.

I shouldn’t be sweating – it’s not hot – and when I push the covers down to my waist, I immediately feel the cold.

I shouldn’t be sweating – it’s not hot – and when I push the covers down to my waist, I immediately feel the cold.

Now I’m in two different climates: from the waist-down, I’m too hot, and from the waist-up I’m freezing.

Here’s a side-effect of the Aropax – hot flushes.

I’m only thirty or so, and struggling to reconcile what Aropax does to me. There are so many problems, but before I started them I had crippling OCD, and had been agoraphobic and living effectively as a shut-in for five years. This is the trade-off.

It doesn’t seem fair there has to be a trade-off – can’t something just be a benefit? It seems I’ve lost so much time, so many opportunities, so much normality, to mental health, and now the counter is equally debilitating.

Something else that has emerged is this casual apathy. A lot of people say mental health medication dulls their mind. Maybe it’s not so much dullness, but a way of smoothing the edginess so that you can function in society without all the trepidation, self-awareness, and rumination.

That’s how I was able to overcome my agoraphobia – with a newfound level of arrogant indifference, and an ability to be cavalier about panic attacks growing resurgent.

Sometimes, I think this is who I was meant to be if I’d never had mental health issues. I want to say I’m confident and assured, and there’s a stream of that in my behaviour, but I know it’s not as straightforward as that because of the other thoughts that creep in.

I vow to myself that if I haven’t succeeded in writing by the time my parents have passed – which, given their age, could take as little as one day (if something dire occurs, like a heart attack of stroke), or as much as twenty-five years (if they enjoy longevity) – then I’ll take my life.

There’s no shock in the thought. It’s so commonplace, that it’s less of a thought, and more an observance of something that’s going to be done, like waking up and brushing my teeth, or eating meals, or breathing.

It just is.

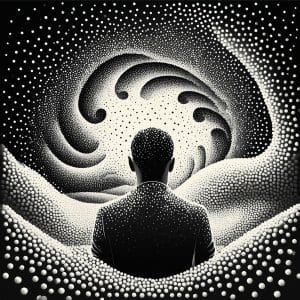

I stare into the bleakest abyss with only the mildest curiosity.

And blossoming out of that is a new certainty.

One night, while out with friends at a bar drinking beer, talk turns to death. One friend travels lots for work, flying all over the country. He’s sure that before he’s forty, he’ll die in a plane crash.

I think I’m sure I’ll be a suicide before forty, but I don’t say it. I don’t tell the others. I don’t want the conversation turning to people assuring me how much I have to live for, because this isn’t about engendering sympathy or manipulating encouragement.

While the notion remains, it extrapolates qualifications – watching friends who married and progressed in their jobs or built their careers while I was a shut-in; writing but not getting anywhere because I’m not good enough; or being mishappen socially by all the mental health issues over the years.

And all the qualifications aren’t just insecurities, or paranoia, but rooted in some form of absolutism, so they grow progressively entrenched, until this surely becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

It doesn’t happen, of course.

My sentence on Aropax is five years, and after the horrible withdrawal, that suicide ideation dissipates.

But the qualifications don’t.